Answer: When you're an astronomer!

"What??!", I hear you cry.

Let me explain. Most of the matter in the universe is in the stars. (Let's

not get into the "dark matter" controversy here.

The issue of "dark matter" is addressed in the following page under

my "Astronomical stuff" menu, i.e.

Quasars: some thoughts....

Scroll a little over halfway down that page to find a link to a web-page

which mentions it, in connection with a related issue: the "big bang".

Because hydrogen and helium are the most common substances in the universe

(with other elements, produced by further fusion, coming a long way behind),

as far as astronomers are concerned, these two are by far the most

important. Somewhat arrogantly, they refer rather dismissively to anything

else as "metals".

This means that not only lithium (element 3 in the periodic table) and

beryllium (element 4) are metals (which they definitely are, in the more

usual sense of the word), but also the next few elements: boron, carbon,

nitrogen, oxygen, and fluorine.

Fluorine?

The chemical elements (of which there are 92 definitely known to

occur naturally on Earth, the last being uranium) can be divided into two

main classes: metals and non-metals.

UPDATE, 18th July 2006

I've just seen

this page

by Bill Beaty, which takes issue with that last assertion (regarding 92

elements on Earth). Scroll about two-fifths of the way down to read his

article "CORRECTED: there are not 92 elements on Earth".

Having just typed "technetium promethium" into Google, I've turned up

this page

(among other equally provocative articles!).

MORAL: Don't believe everything you read. Keep your mind OPEN! That

way, we can all learn something new every day, and gradually increase the

sum of human knowledge and understanding.

“FEED YOUR HEAD”

There are some elements, known as semimetals or

metalloids

,

which can exhibit both metallic and non-metallic properties under certain

conditions. These include boron (already mentioned above), silicon,

germanium, arsenic, antimony, tellurium, and polonium. (Some sources

classify polonium as a metal.)

Some of the metalloids (notably silicon and germanium) are

semiconductors, which means that they conduct electricity (fairly)

well under some conditions, and rather badly under others. This makes them

useful in the manufacture of electronic components such as diodes,

transistors, and integrated circuits. In recent years, arsenic has become

very important, especially in combination with other elements - notably

gallium and phosporus. Some modern very bright light-emitting diodes (LED's)

rely heavily on arsenic compounds; and gallium arsenide can convert

electrical energy directly into coherent light, thus forming the basis for

LASER LED's (which are important in our modern world, as they are what make

CD players, CD-ROM drives, DVD players etc. possible).

When I first heard about arsenic, in some story or other about people being

poisoned, I asked my Dad what it was. He said it was "when somebody pinches

your bottom" (which, of course, immediately elicited a shocked exclamation

from my Mum.)

[If you speak Aussie English, New Zealand English, or any of the many

variants of English English, you'll probably understand what this is about.

On the other hand, if you're a speaker of American English or similar, it

may all be a bit of a mystery to you...]

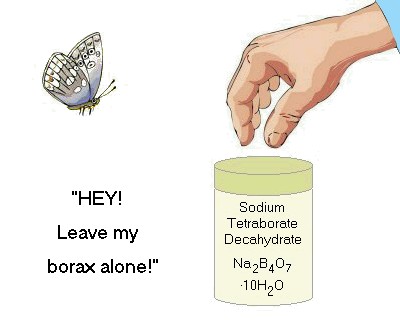

Sort of reminds me of the kid who wrote in a test that the way to kill an

insect is to

pinch its borax...

While on the subject: you may like to have a look at these two web-pages

(not for those with delicate sensibilities):

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arsole

>>> Back to business... <<<

Metals are generally malleable (can be hammered into thin sheets) and

ductile (can be drawn out as a wire). But by far the most obviously

important property that they share is that they conduct electricity quite

well - very well, in some cases. Silver is the best conductor; copper is

excellent; and

gold

isn't too far behind, followed by aluminium in fourth place.

The outermost electrons in metal atoms are rather loosely bound, in the

sense that in a lump of metal, these electrons are fairly free to roam

around within the lump and over its surface. This accounts for the shiny

appearance of metals.

Metals are electro-positive - they can readily give up one or more

electrons to other atoms which are more electro-negative. This might

mean another, less electro-positive, metal; various kinds of true

intermetallic compounds may form, with specific ratios of component

metals - or they may be alloys of various compositions, in which

atomic and inter-atomic geometry plays a part similar in importance to pure

electronic bonding. But the more obvious ways metals form compounds is with

non-metals.

Non-metallic elements are those which have nearly-filled outer electron

shells - as opposed to the situation in metals, which have nearly-empty

outer electron shells. Non-metals are "happy" to accept electrons from

metals, which are "happy" to donate them. (Excuse the silly

anthropomorphism!) Thus ionic bonds can form, and the atoms combine

to become a compound.

Just as some metals are more electro-positive than others, so some

non-metals are more electro-negative than others. Compounds can certainly be

formed from non-metals. The most obvious is water - good old

H2O.

There are only 18 (known) non-metallic elements (including hydrogen and

helium). Five of them form compounds by accepting just one electron from

other atoms. These reactive elements are collectively known as the

halogens. The most commonly-known one is chlorine, which is a

component of ordinary salt and essential for the life of most if not all

animals (including humans).

Chlorine, a green gas, has atomic number 17. The other halogens which have

higher atomic numbers are bromine, a red liquid; iodine, a dark bluish-grey

waxy solid which produces violet fumes; and astatine, which is a radioactive

solid.

Of these, chlorine is the most reactive. By itself, it's quite toxic, and

was once used as a poison gas, notably in World War 1. Certain fairly

unstable chlorine compounds (which slowly release elemental chlorine) are

used in bleach and as a disinfectant to kill micro-organisms in swimming

pools - even, in small concentrations, in drinking water.

Going down the list, bromine is less electro-negative, iodine still less so,

and astatine still less so again. (Some sources even describe astatine as a

metalloid - which brings the number of non-metals down to 17.)

They're all similar to each other in some ways. I don't know much about

astatine; it's radio-active and not as well-known as the others. They're all

toxic in varying degrees, which means that they may have some medical uses

in carefully-controlled quantities. Iodine has long been used in ointments

for dressing wounds, as a disinfectant; and it's important to humans in that

an iodine deficiency can lead to a medical condition known as goitre

(enlargement of the thyroid gland).

They all have similar "chemical" smells, presumably because they interact

with olfactory sensors in the nose in similar ways. Interestingly, ozone,

O3, a form of oxygen which has three atoms

per molecule instead of the usual two, smells a bit like the halogens, with

which it shares certain chemical properties.

Ozone is produced by the action of ultra-violet light on oxygen (hence the

"ozone layer" in the upper atmosphere), or when a high-voltage spark occurs

in ordinary air, as a result of the breakdown and recombination of

O2 molecules. It's not considered a good idea

to breathe too much of it; freaky people such as myself who have an interest

in

high-voltage electricity

are advised

to have a window or door open when generating ozone.

Two interesting and informative web-pages with more details about ozone are

here

and

here.

There is one other halogen: fluorine (atomic number 9), which comes

before chlorine in the periodic table. This is seriously dangerous

stuff.

It is a pale yellow gas. It attacks just about anything; for example, it can

combine with

xenon,

one of the inert gases, in various proportions to form a number of different

compounds. (Admittedly, some such compounds are not particularly stable; but

the fact that they will form at all is highly significant.) Many of

fluorine's reactions are at least violent, and may often be explosive.

Fluorine was finally isolated by the French chemist Henri

Moissan

in 1886, by electrolysis - the only way to rip it out of its compounds. It

is so electro-negative that no chemical means will shift it. Earlier

researchers had managed to isolate simple compounds of fluorine by chemical

means - toxic and/or explosive substances which were also very dangerous -

but most sources agree that Moissan was the first to isolate the element.

He, along with some of these other researchers, suffered injury as a result

of exposure to the substance.

Here

is a website which has more information about the element.

Fluorine is the most reactive element of them all - and it is definitely a

non-metal. To go anthropomorphic again, it "views" everything else - even

the other halogens - as electro-positive. (To see a page with some

information about compounds containing only chlorine and fluorine, click

here

.)

So, a definition of an astronomer is: someone who calls fluorine

a metal.

Strange people...!

UPDATE, Friday, 2nd January 2009

Having very recently figured out that I can access YouTube videos and

suchlike on my computer (a Windows 98 machine, since my old "95" died a

while back), I've found to my huge delight that there are several versions

of

Tom Lehrer's

"Elements" song out there for the viewing/listening. So I've decided to put

links to a few of them here.

The song, written in 1959, lists all the elements known until then (as far

as element 102, nobelium), to the tune of Gilbert and Sullivan's "Modern

Major General" (from "Pirates of Penzance"). If you'd like to read the

lyrics, click

here.

The

first

video is a very funny cartoon version, with Tom Lehrer's own voice

providing the soundtrack. The visuals accompanying the list of elements are

brilliantly done; you really have to concentrate to take it all in.

The

second

has some similarity with the first, but has still photographs of Tom

instead of cartoon animation. Again, you need your wits about you to fully

appreciate the tightly-packed information on-screen!

The

third

is done by (I think) a sixteen-year-old girl who gives a very creditable

performance, with some amusing text comments scattered throughout.

The

fourth

is an unashamedly "Milli Vanilli"-style version done by a twelve-year-old.

I'm quite sure that to do this as well as it's done here requires a

considerable amount of real talent, a strong sense of timing, and a great

sense of humour.

The

fifth

is the icing on the cake. The performer, only four years old, struggles a

bit - but perseveres and ultimately pulls off an amazing achievement. Then,

to add insult to injury, he confidently reels off the names of all elements

discovered since the song was written, in 1959! Absolutely incredible...

There are other versions out there, too. You have to admire people who can

do this even tolerably well. Many of the elements have long names,

which may be tongue-twisters in their own right - for example,

"praseodymium" has six syllables. You try fitting the names of the

first 102 elements into a two-minute performance, with or without musical

accompaniment!

*

*

*

*

*

One more, just to put the whole matter in some sort of more-or-less serious

perspective:

This version

again features Tom Lehrer's original version of the song. The very simple

graphics accompanying the music simply show an "empty" periodic table being

completed, one element at a time, just as each is mentioned.

This version appeals to me, for a very good reason. If I may brag just a

little bit, just over a year ago I finally memorized the entire periodic

table - at least up as far as some of the recently-discovered elements - to

the point where I can actually sit down and write the whole thing out from

memory (and if you're not impressed, you jolly well should be!

My home page

Preliminaries (Copyright, Safety)

When is a metal not a metal?

)

Stars are made up mostly of hydrogen, which is fusing into helium

(initially).

)

Stars are made up mostly of hydrogen, which is fusing into helium

(initially).

UPDATE-WITHIN-AN-UPDATE, 3rd January 2009:

I've recently figured out how to render my old computer "YouTube capable";

and just today I've been delighted to find a video of Jefferson Airplane

performing "White Rabbit", the last line of which you have just read

(above). To see Grace and the gang in full flight, click on the bunny.

UPDATE-WITHIN-AN-UPDATE, 3rd January 2009:

I've recently figured out how to render my old computer "YouTube capable";

and just today I've been delighted to find a video of Jefferson Airplane

performing "White Rabbit", the last line of which you have just read

(above). To see Grace and the gang in full flight, click on the bunny.

To continue:

Profuse apologies in advance for the next few lines. I know it's all a bit

silly, but I can't resist it.

By far the majority of the other elements are metals, in the ordinary

everyday sense. They tend to be dense, i.e. heavy for their size (although

two of them, lithium and sodium, are light enough to float on water). Most

of them are solid under normal conditions; mercury is an obvious exception -

and gallium melts at just below 30 degrees C, so it too will be a liquid on

a really hot day. (A teaspoon made from gallium would be useless for

stirring a hot drink.  )

)

) - and it's fun to be able to watch the table

being filled in, and actually be able to follow the action!

) - and it's fun to be able to watch the table

being filled in, and actually be able to follow the action!

Return to Astronomical stuff menu

Return to Astronomical stuff menu